Agathosma pattisonae

Agathosma pattisonae Dümmer

Family: Rutaceae

Common names: boulder buchu (Eng.); klipboegoe (Afr.)

Introduction

The boulder buchu is a rigid, aromatic, rock-squatting Agathosma only known from the Cedarberg in the Western Cape. Unique in its cliff and boulder habitat, growing in areas where fire cannot reach. When mature, the plant is covered in star-shaped pink flowers in spring and early summer.

Fig. 1. A close-up of the flowers of Agathosma pattisonae, growing on a south-facing cliff in the Cederberg.

Description

Description

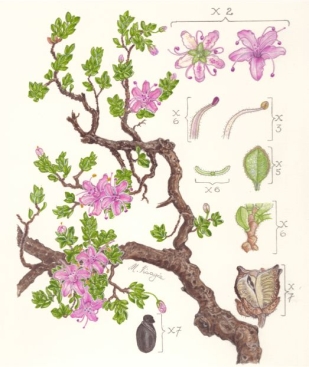

Agathosma pattisonae is a compact, rigid, rock-squatting, cliff-hugging, slow-growing shrub, to about 1 m across and about 150 mm high, with a single main stem up to 40 mm in diameter. The older branches are longitudinally fissured, grey-brown, and the younger branches are pale green, becoming tan-brown. The surface of the young branches is covered with fine hairs (puberulous). The spreading ascending leaves are densely arranged, alternate, obovate 5–7 × 3–5 mm, smooth (glabrous), with a tough leathery texture. The upper surface of the leaf is concave, especially in exposed situations. The leaf margin with distinctive glands, which can also be found scattered on the upper and lower surface. The leaf petioles are short, about 1 mm long, the base with a pulvinus (a joint-like thickening). The leaf tip with a short, sharp point. The flowers are pale to dark pink, solitary in the axils of the upper leaves, up to 20 mm across. The petals to 10 mm long, oblong, with dark, maroon-red gland-dots on the under surface as well as towards the tip of the upper surface. The petal tips grow reflexed, rarely concave towards the tip, the base sessile. The sepals 3–4 mm long, egg-shaped, smooth (glabrous), with submerged glands, the margins very thin, hyaline, with fine hairs like eye-lashes. The pedicels are short, up to 8 mm long, finely hairy, green, subtended by 2 lance-shaped bracts and 2 bracteoles. The staminodes are up to 6 mm long, oblong, with a dark, maroon-red apical gland at the apex, the tips incurved. The stamens to 8 mm long, the anthers yellowish-brown during flowering, with a large gland between the two anther loci. The disk is a shallow saucer-shape. The ovary with 5 glabrous carpels. The style smooth, cream-coloured, to 4 mm long, deflexed from the centre of the flower. The stigma simple, maroon-red. The fruiting body consists of a capsule to 4 mm long, its surface is warty and covered in translucent (see-through) glands. The seeds are 3.5 mm long, smooth, black and glossy with a well-developed elaiosome.

Fig. 2. An illustration of Agathosma pattisonae by Marieta Visagie, from a plant growing on a sheer cliff on the eastern slopes of the Cederberg, near the Wolfberg Arch.

Conservation Status

Status

Agathosma pattisonae is only known from a few sites along the eastern slopes of the Cederberg. In 2009 it was classified in the Red List of South African Plants as Data Deficient – Insufficient Information because its distribution and habitat were too poorly known to evaluate its status. However, we now know that this plant is confined to only some cliffs, in an area of about 10 km². Its distribution falls within in the Cederberg reserve, a protected area, and therefore, it can be categorized as Rare.

Fig. 3. The cliff-face habitat of Agathosma pattisonae before the devastating fire. The plants have deep roots that penetrate the crevices on cool, south-facing cliffs on the eastern slopes of the Cederberg.

Distribution and habitat

Distribution description

Agathosma pattisonae is one of many taxa confined to the Cape Floristic Region. It is only known from a range of about 10 square kilometre on the eastern slopes of the southern part of the Cederberg, growing in Cederberg Sandstone Fynbos (Mucina & Rutherford 2006). The plants grow in a narrow band at altitude of about 1 300 to 1 400 m, below the Wolfberg Arch on the Joubert Hiking Trail (Slingsby Cederberg Map, Manning & Goldblatt 2012). Its habitat is exclusively quarzitic sandstone rock faces and boulders (Fig. 2). Seeds germinate in crevices, the roots deeply penetrating the rock crevice and entering hairline cracks. The habitat consists mostly of cooler, south-facing aspects but plants are also seen growing on top of boulders or on other slopes.

Fig. 4. Terry Trinder-Smith, Agathosma specialist, examining an Agathosma pattisonae plant in full flower, growing on a south-facing, sandstone cliff face near the Wolfberg Arch, Cederberg.

Derivation of name and historical aspects

History

Hugh Taylor in his Cederberg Vegetation and Flora, recorded 1 778 species growing wild in the Cederberg (Taylor 1996). Agathosma pattisonae belongs to the citrus family, Rutaceae, which is especially well represented in the Cederberg; of the 70 species, in 10 genera, recorded for this plant family , 40 of these belong in the genus Agathosma. Among these is the well-known buchu, or boegoe (Agathosma betulina), which is a popular medicinal plant, often harvested for its essential oils (Van Wyk et al. 1997, Watt & Breyer-Brandwijk 1962).

In August 2011, a sterile specimen of an Agathosma was brought in to botanist Terry Trinder-Smith at the Bolus Herbarium, Cape Town (see Fig. 4). It was collected by the retired ophthalmologist, Dr Ivor Jardine, a keen botanist who has made many plant collections from the southern Cederberg, contributing towards our knowledge of plants in this part of the world. Ivor collected his specimen from a cliff face north of the Wolfberg Arch. At first it was thought to be a species new to science. This inspired Ivor to further investigate and in October 2012 he collected more material of this species, this time with a few flowers, and it was established by Terry that it certainly represents Agathosma pattisonae, a rare endemic, only known from a single herbarium specimen gathered by Florence Pattison in 1913 and named by the Cape Town botanist, Richard Dümmer (1887–1922) in 1920 in the Annals of the Bolus Herbarium (Dümmer 1920, Gunn & Codd 1981).

Fig. 5. Agathosma pattisonae growing together with Crassula atropurpurea, on a south-facing cliff, on the eastern slopes of the Cederberg.

A subsequent visit to the site in the Cederberg in November 2013 was then arranged to further investigate. The plants were reached along the Joubert Hiking Trail, near the Wolfberg Arch. This time accompanied by the author, Terry Trinder-Smith, Messrs Hartwig and Andrag. Although we were fortunate to encounter the plants in full flower, no fruiting material could be found (see Figs 4 & 5). Mr Andrag was able to return to the site at the end of December (of that year) and found material that was in fruit, with mature seeds.

The author, interested in cliff-dwelling plants, realised its significance as an obligatory cliff-dweller and decided to further investigate and re-visited the site in February 2014, together with Ernst Hartwig, Tielman Haumann and party. He was amazed to find some plants still flowering, however most were in the process of developing fruiting bodies. He also noticed that, after fertilization, the fruits bend towards the cliff face (see Fig. 7) and are not ascending as in most other species of Agathosma. He decided to get this plant illustrated, returning to the site November 2017 with Peter Jansen from the Stellenbosch University Garden to collect fresh material (E.v.J. & Jansen 27572) for illustration purposes by botanical artist Marieta Visagie, who prepared the accompanying plate. To our dismay we found that a fire had just burned through and had destroyed most of the surrounding fynbos vegetation (Fig.7) . However, most of the Agathosma pattisonae plants grow on boulders or cliffs where the fire did not reach, and most of these plants were flowering in profusion and we were able to collect fresh material for Marieta Visagie as well as cuttings to propagate the plant (Fig. 8). Some of the plants that were in reach of the fire were scorched or killed, but the majority of the population survived. This plant is clearly not a re-sprouter and is dependent on its fire-free, cliff habitat.

Fig. 6. The habitat of Agathosma pattisonae after a fire. Notice the plants on the cliff face unscathed by the fire.

Ecology

Ecology

The Cederberg is known for its mineral-poor, quarzitic, sandstone rocks, summer-dry climate and unique assemblage of fire-adapted fynbos species. The tallest is the Clanwilliam cedar (Widdringtonia wallichii), often growing on mountain tops among large boulders where fires cannot reach or only partially reach. When in reach the fire certainly incinerates the plant, which has to start again from seed. Another strategy that plants employ to cope with fire is resprouting, of which there are many examples such as the king protea (Protea cynaroides) or the many geophytes, which simply resprout from an underground lignotuber, bulb or corm.

Plants that only grow on cliffs, and especially the non-succulent plants such as Agathosma pattisonae, have to grow and reproduce successfully in this challenging environment, and they are thus highly specialised. Three types of obligatory cliff-dwelling plants (cremnophytes) have been identified on cliffs in southern Africa (Van Jaarsveld 2011). The hangers which surrender to gravity and have pendent stems or leaves; the cliff-huggers which have a low cushion-like growth habit, forming clusters and often rooting at nodes; and the cliff-squatters, which are solitary shrublets with ascending to hugging stems. Agathosma pattisonae is a squatting cliff-dweller with hugging stems and is often cushion-shaped.

Fig. 7. An old, mature specimen of Agathosma pattisonae hugging a south-facing cliff face on the eastern slopes of the Cederberg.

Most plants are only mobile when in their seed form and they have evolved many different dispersal methods. For the plants which have made cliffs their home, the dispersal of its offspring is tricky. The cliff habitat demands special adaptations. Although the near vertical surface does not allow efficient water retention, cliffs provide a safe haven devoid of larger herbivores and fire. Small wonder that the majority of obligatory cliff-dwellers (cremnophytes) are succulents, which enables them to survive on stored moisture during the dry season. However there are also non-succulent obligatory cliff dwellers, of which the rare Cederberg endemic, Agathosma pattisonae, is a good example. To these non-succulent plants, obtaining sufficient moisture and surviving the dry months demands special adaptations. In the case of our species this includes a sufficient root system penetrating int the crevices and hairline crevices Most plants grow on south-facing aspects where moisture is retained longer than for instance on sun-exposed northern surfaces.

Fig. 8. Agathosma pattisonae has deep roots that penetrate the crevices of cool, south-facing cliffs on eastern slopes of the Cederberg.

Most of the fynbos plants have small, linear leaves, which is an adaptation to the long, dry summers. The leaves of A. pattisoniae are small, leathery with volatile oils, and are well adapted to the long, dry summers.

The flowers of Agathosma pattisonae are most striking, being large, bright pink and with the plants being particularly floriferous (see Figures 1, 4 & 5). Plants growing on cliffs also tend to produce larger flowers promoting visibility for effective pollination (Snogerup 1971) which we expect are insects. Another interesting feature about these plants is their aromatic volatile oils. Terry Trinder-Smith says A. pattisonae smells like almost cured pipe tobacco. When fresh leaves are crushed the same, yet far less intense, odour is exuded.

Plants growing on cliffs also tend to have specialist seed dispersal strategies. How does the seed end up in crevices on cliffs? Agathosma is known to disperse its seeds explosively, shooting them away from the plant. Differing from all other known species of Agathosma, after fertilization the fruiting bodies (seed capsules) of A. pattisonae bend towards the cliff face and not unlike two other obligatory cliff or boulder dwellers, the Namaqua klipblom (Colpias mollis) and the invasive ivy-leaved toadflax (Cymbalaria muralis), the latter known to so many Capetonians as a garden weed . The latter growing on limestone cliffs in the Mediterranean and which became a weed on many vertical walls in Cape Town. The seeds in the case of many species of Agathosma are expelled explosively. If this is also true for A. pattisonae, this explains its strategy of the fruiting bodies bending towards the cliff (away from the light) expelling the seed towards the cliff face and likely into crevices thus ensuring establishment in this secure habitat. The seeds of Agathosma have an elaiosome, a fleshy appendage that attracts ants and a leads to a phenomenon known as myrmechochory. The ants carry the seeds to their nest and in turn facilitate germination. It is not known whether ants play a role dispersing the seed. A. pattisonae.

Fig. 9. The fruits of Agathosma pattisonae all point towards the cliff face.

A cliff-dwelling lizard noticed and photographed in the habitat of Agathosma pattisonae (Fig. 12 ) was the melanistic endemic Cederberg Cliff Lizard (Hemicordylus robertsi) with its long limbs and tail, well adapted to life on a vertical cliff (Mouton, L. et al 2014). Recently (2019) another related lizard on the Drakensberg (Pseudocordylus subviridis) has been identified as the main pollinating agent of Guthriea capensis along the Drakensberg Escarpment (Cozien et.al.). The colourful Augrabies Flat Lizard (Platysaurus broadleyi) is fond of the fruits of Ficus cordata (Burrows & Burrows 2003). Large groups of this social lizard can be seen along the rocky gorge at Augrabies Falls, where Ficus cordata is not uncommon. These lizards also play a role in dispersing the seed to crevices where it can germinate (Greef & Whiting 1999, Branch 1998). Could the Cederberg Cliff Lizard play a role in the seed dispersal of Agathosma pattisonae?

Fig. 10. The Cederberg Cliff Lizard (Hemicordylus robertsii) noticed in the habitat of the Boulder Buchu (Agathosma pattisonae).

Uses

Use

There are no known medicinal or cultural uses of this rare, and little-known plant.

Growing Agathosma pattisonae

Grow

Attempts by botanist and horticulturist Peter Jansen to grow this plant from cuttings have failed. It still has to be grown from seed and tested in cultivation and it is expected to be difficult to simulate its cliff face habitat. If a method of successful propagation can be found, Agathosma pattisonae would be ideal for dry stone walls in fynbos gardens (Van Jaarsveld 2010).

References

- Branch, B. 1998. Field guide to snakes and other reptiles of southern Africa. Struik. Cape Town.

- Christenhusz, M.J.M., Fay, M.F. & Chase, M.W. 2017. Plants of the World, an illustrated Encyclopedia of vascular plants. Kew Publishing, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew.

- Clarke, H. & Charters, M. 2016. The illustrated dictionary of southern African plant names. Flora & Fauna Publications Trust, Jacana, Johannesburg.

- Cozien R.J., Van der Niet, T,. Johnson S.D. & Steenhuisen, S. 2019. Saurian surprise: lizards pollinate South Africa’s enigmatic hidden flower Ecology 100(6).

- Dummer, R.A. 1920. A further contribution to our knowledge of the genus Agathosma, Willd., containing descriptions of 23 new species and 3 new varieties. Annals of the Bolus Herbarium 3: 44–62.

- Greef, J.M. & Whiting, M.J. 1999. Dispersal of Namaqua Fig (Ficus cordata) seeds by the Augrabies Flat Lizard (Platysaurus broadleyi). Journal of Herpetology 33, 2: 330–334.

- Gunn, M. & Codd, L.E. 1980. Botanical exploration of southern Africa. Balkema, Cape town.

- Manning, J. & Goldblatt, P. 2012. Plants of the Greater Cape Floristic Region 1: the Core Cape Flora. Strelitzia 29. South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria.

- Mouton, P.N., Bates, M.F. & Whiting, M.J. Reprint 2014. Hemicordylus capensis, Family Cordylidae, in Atlas and Red List of the Reptiles of South Africa, Lesotho and Swaziland. Suricata 1.

- Mucina, L. & Rutherford, M.C. (eds) 2006. The vegetation of South Africa, Lesotho and Swaziland. Strelitzia 19. South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria.

- Picker, M., Griffiths, C. & Weaving, A. 2002. Field Guide to the Insects of South Africa. Struik Publishers, Cape Town.

- Pillans, N.S. 1950. A Revision of Agathosma. Journal of South African Botany 16: 55-183.

- Raimondo, D., Von Staden, L., Foden, W., Victor, J.E., Helme, N.A., Turner, R.C., Kamundi, D.A. & Manyama, P.A. (eds) 2009. Red list of South African plants. Strelitzia 25. South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria.

- Snogerup, S. 1971. Evolutionary and plant geographical aspects of chasmophytic communities. In P.H. Davis, P. Harper & I.C. Hedge (eds), Plant life of South-West Asia: 157–170. Botanical Society of Edinburgh.

- Taylor, H.C. 1996. Cederberg Vegetation and Flora. Strelitzia 3. National Botanical Institute, Brummeria, Pretoria.

- Van Jaarsveld, E.J. 2010. Waterwise gardening in South Africa and Namibia. Struik, Cape Town.

- Van Jaarsveld, E.J. 2011. Cremnophilous succulents of southern Africa: diversity, structure and adaptations. Unpublished Ph.D.Thesis, University of Pretoria.

- Van Wyk, B.E., van Oudtshoorn, B., Gericke, N., 1997, Medicinal Plants of South Africa, Briza Publications, Pretoria.

- Watt, J.M. & Breyer-Brandwijk, M.G. 1962. The medicinal and poisonous plants of southern and eastern Africa , edn 2. Livingstone, Edinburgh & London.

Credits

Ernst van Jaarsveld

Kirstenbosch National Botanical Garden (Retired 2015)

Babylonstoren Farm

Extraordinary senior lecturer and researcher,

Department of Biodiversity and Conservation, University of the Western Cape

September 2022

Plant Attributes:

Plant Type: Shrub

SA Distribution: Western Cape

Soil type: Sandy, Loam

Flowering season: Spring, Early Summer

PH: Acid, Neutral

Flower colour: Pink

Aspect: Morning Sun (Semi Shade), Afternoon Sun (Semi Shade)

Gardening skill: Challenging

Special Features:

Horticultural zones

Rate this article

Article well written and informative

Rate this plant

Is this an interesting plant?

Login to add your Comment

Back to topNot registered yet? Click here to register.