Hibiscus waterbergensis

Hibiscus waterbergensis Exell

Family: Malvaceae

Common names: Waterberg hibiscus (Eng.); Waterberg hibiscus (Afr.).

Introduction

As a neat, upright, little-branched shrub of about 1.5 m tall, with its greyish-green appearance and vibrant scarlet-red flowers in summer, Hibiscus waterbergensis is a worthy plant to try and cultivate in medium to small sized gardens. It will truly be exquisite to see this plant, a near endemic from the Waterberg, in cultivation.

Fig. 1. Hibiscus waterbergensis flower. A. Flower viewed from below (Photo A Frisby); B Close-up view of calyx (larger) and epicalyx (smaller) lobes (Photo M Popp); C, D & E. Flowers viewed from various sides (Photo C: SP Bester, D: J Kalwij, E: L Lindenthal).

Description

Description

An erect shrub or subshrub or slender annual herb, 1−2 m high, with few branches. Branchlets densely covered with a very fine indumentum of minute stellate hairs, eventually becoming glabrous or nearly so (glabrescent). Leaves ash-grey or yellowish, stipulate with subulate stipules 2.5−4.0 mm long, petiolate, with petioles 2−10 mm long, densely covered in star-shaped hairs; leaf blade chartaceous, ovate to broadly ovate or ovate-elliptic, 15−35 Í 10−30 mm, densely covered with minute stellate tomentum on both surfaces, margins serrate (sharply toothed), apex rounded or truncate, 5-veined, midrib slightly prominent above, prominently so beneath, with veins inconspicuous above and prominent beneath.

Fig. 2. Leaves of Hibiscus waterbergensis. A. Underside of leaves showing noticeable ventral raised venation and toothed margin (Photo SP Bester). B & C. Upper side of leaves showing indumentum and relative indistinct venation on dorsal side of leaves compared to ventral side (Photo B: SP Bester, C: M Popp).

Flowers grow from the axils of leaves (axillary), are solitary, and bright scarlet−red , with pedicel up to 35 mm long, minutely hairy, articulated near the apex, 7−8 mm long. Epicalyx 7−8, triangular to elongate-triangular, 2.0−2.5 mm long. Calyx 7−8 mm long, with elliptic or lanceolate-elliptic lobes. Petals oblong-elliptic, about 15−20 Í 5−6 mm, externally stellate-pilose, glabrous internally. Staminal tube 5 mm long. Filament parts free, 2.0−4.0 mm long. Style tip deeply 5-lobed, each branch ending in a globose stigmatic surface. Ovary ellipsoid, 4 Í 3 mm, with style branches 1.5−4.0 mm long.

Fig. 3. Floral morphology of Hibiscus waterbergensis. A. Ventral view of flower showing epicalyx (7 or 8 elongate to triangular-elongate lobes – smaller petaloid lobes) and calyx (elliptic or lanceolate elliptic petaloid lobes – larger lobes); B. Side view of staminal tube with numerous anthers fused into a column; also showing 5-branched style tip with hirsute stigmatic surface; C. Side view of branch with pedicel and flower – note the articulation on the pedicel close to the base of the flower; D. Side view of branch with leaf. (Photos SAPlants@Wikicommons)

The peak flowering period is in early summer, from October to December, but plants are very dependent on spring and summer rainfall, so flowering has also been observed from mid-summer to autumn (November to April).

Fruit a sub-globose loculicidal capsule, 12 mm in diam., minutely pubescent. Seeds, kidney-shaped, 2.0−3.0 Í 1.5 mm, densely covered in 2−5 mm long cottony silky hairs.

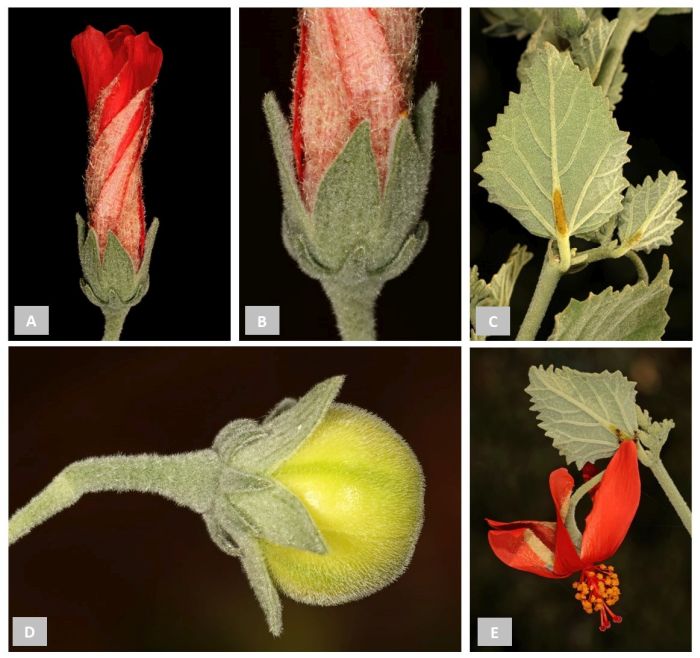

Fig. 4. Floral morphology of Hibiscus waterbergensis. A. Flower bud with twisted corolla lobes unevenly furnished with stellate hairs; B. Base of flower bud showing the epicalyx (numerous small bractoidal lobes) and calyx (fewer large petaloid lobes); C. Leaf showing extrafloral nectary on base of main vein; D. Fruit in side view; E. Flower and leaf in side view (Photos SAPlants@Wikicommons).

The size of the flowers, them being pendulous and the leaves with the two large patches of extrafloral glands immediately distinguish the Waterberg hibiscus from any of the other red-flowered species found in its natural distribution range.

Conservation Status

Status

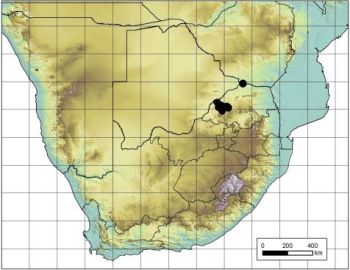

The conservation status of this species is assessed as Least Concern (LC) by the Red List of South African Plants, as it is widespread in the Waterberg and with the single known location at Mapungubwe results in a wide distribution range. Seemingly no threat has been observed. The Waterberg region, where this species is found, includes numerous protected areas which help in the conservation of endemic species like Hibiscus waterbergensis. Yet, only a few collections have been made that ended up in herbaria. The populations are believed to be stable and not declining, and hence, the conservation status assessment of LC is justified. Suitable habitats between the Waterberg and Mapungubwe exist, yet no further populations have thus far been collected or observed in the area between these two regions.

Fig. 5. Known distribution of Hibiscus waterbergensis based on the herbarium specimens.

Distribution and habitat

Distribution description

Hibiscus waterbergensis is indigenous to South Africa and the only endemic Hibiscus in the Limpopo Province. Herbarium specimens and observations have mainly been from the Waterberg with a single disjunct distribution in Mapungubwe northwest of the Soutpansberg.

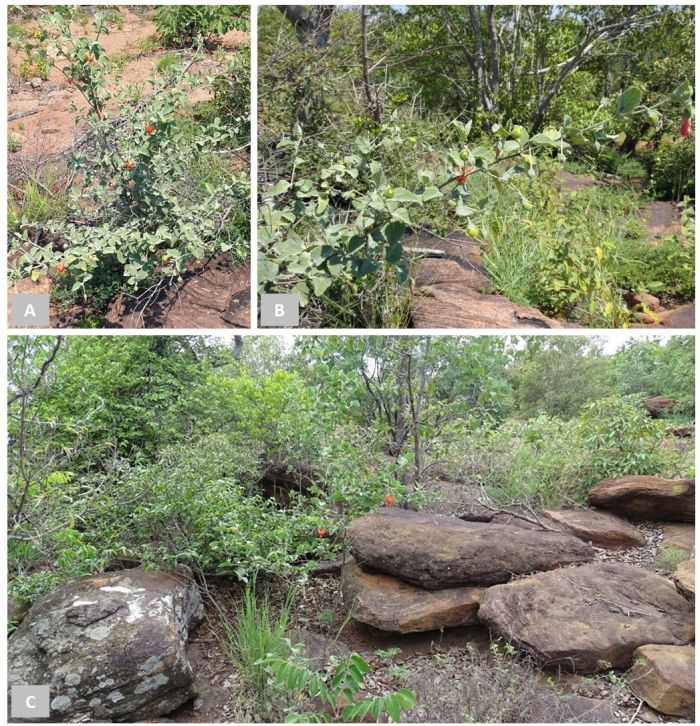

This species is an herbaceous shrub that thrives in light shade to full sun, especially on rocky outcrops on slopes of varying inclination. It occurs predominantly on southern and southwestern aspects of hills and occasionally on streambanks. The habitat comprises sandy to loam soils derived from quartzite or sandstone. The reported altitude range is approximately 800−1 200 m above sea level.

Fig. 6. Habit of Hibiscus waterbergensis in habitat. A (Photo J Kalwij), B (Photo M Popp), C (Photo M Pienaar)

Derivation of name and historical aspects

History

The generic name Hibiscus is a Greek name for the marsh mallow and the epithet waterbergensis is pertaining to the area from which it was originally described. The charismatic genus Hibiscus, comprising approximately 300−440 species and is a member of the Malvaceae family. One of the outstanding characteristics of members of Hibiscus is the stamens that are fused into a tubular column through which the style protrudes at the top. Hibiscus is regarded as a medium-sized genus, ranging from annual herbs to large trees, although most species are perennial sub-shrubs. Hibiscus is represented by 57 taxa indigenous to southern Africa, with 16 taxa endemic to the region. Thirty-five taxa are indigenous to the northern Provinces of South Africa (Northwest; Limpopo, Mpumalanga and Gauteng) with the majority (32) occurring in the Limpopo Province.

The other small, red-flowered species that could be encountered in the northern Provinces of South Africa include H. praeteritus and H. coddii subsp. coddii and H. coddii subsp. barnardii. Hibiscus waterbergensis, however, can easily be distinguished from all others by the nodding flowers with angled pedicels and dense mat of interwoven stellate hairs on both sides of the leaves and stem. A number of these taxa are depicted in Figure 7.

Fig. 7. Selection of other small, red-flowered (scarlet) Hibiscus taxa from southern Africa. A. H. praeteritus (Photo SAPlants@Wikicommons); B. H. coddii subsp. barnardii (Photo SAPlants@Wikicommons); C. H. barbosae (Photo J Gallagher); D. H. rhodanthus (Photo G Jamie); E. H. coddii subsp. coddii (Photo T van der Merwe).

Most Malvoideae (one of the nine subfamilies in Malvaceae that includes Hibiscus, Pavonia and Abutilon amongst others) are pollinated by bees or birds or insects. In some members of the Malvoideae (e.g. H. trionum and H. laevis) facultative autogamy has been observed, with similar long stylar branches in H. waterbergensis that could easily result in self-fertilisation is another feature that could be studied. Seeds are probably dispersed by anemochory.

Ecology

Ecology

Despite the plants being perennial, most of the previous season’s growth dies back in winter when the plants become dormant. In the new growing season, plants sprout in response to rainfall, which may vary, and depending on when this occurs, flowering usually occurs between mid-summer to autumn (November to April), but mostly during early summer (November−December).

Fig. 8. Trichomes and nectary of Hibiscus waterbergensis. A & B. Dense indumentum of trichomes consisting of stellate hairs on leaf: A. Adaxial side; B. Abaxial side (Photos SP Bester). C & D. Extrafloral nectary on base of main vein of leaf (abaxial side): C. From herbarium specimen (Photo SP Bester); D. From fresh material (Photo SAPlants@Wikicommons).

In most Malvaceae, the nectary consists of carpets or cushions of multicellular glandular hairs in various parts of the plant. The nectaries that provide rewards for pollinators are commonly found on the inside of the calyx near the base where the corolla is fused to the calyx, and access to the nectar is permitted to a pollinator probing the centre of the flower while simultaneously pollinating the flower. The extrafloral nectaries in Malvoideae consist of aggregations of glandular hairs, either on the lower side of the foliage (as is the case in the Waterberg hibiscus), or the sepals or at the apex of the pedicels. In Hibiscus waterbergensis, the morphology of the extrafloral nectaries is quite homogenous, but other genera in the Malvaceae (e.g. Triumfetta) may have variously shaped extrafloral nectaries within the same species. Extrafloral nectar such as that produced in H. waterbergensis has also been reported in H. praeteritus and accumulates as a drop or few at the dense cushions on the main vein of the underside of the leaf. It has been proposed that this may function to attract insects, either pollinators or predators of herbivorous insects that may attack the plant.

Fig. 9. Ant (Polyrhachis schistacea) harvesting compounds from extrafloral nectaries on the leaves of Hibiscus waterbergensis (Photo SAPlants@Wikicommons).

Uses

Use

Many species and hybrids of Hibiscus are commonly cultivated as ornamental plants, particularly in temperate to subtropical regions. Being regarded as the fifth most popular commercially grown flowering plant globally, following roses, azaleas, carnations, and orchids. Although Hibiscus waterbergensis is not established as a garden ornamental, it shows great promise and would be well suited to bushveld, and grassland gardens.

No medicinal or cultural uses for Hibiscus waterbergensis could be traced in the literature. Other species have various uses such as flexible wood for hut building, fibrous bark for making string, leaves and stalks used to treat urinary complaints and sometimes the flowers are cooked and eaten. Read about the species of Hibiscus covered in this series so far: Hibiscus calyphyllus, Hibiscus coddii, Hibiscus pedunculatus, Hibiscus praeteritus and Hibiscus tiliaceus.

Growing Hibiscus waterbergensis

Grow

Most hibiscus plants can easily be propagated by growing them from softwood cuttings from fresh, new growth of the mother plant. The best time to make these cuttings is from mid-spring to early summer when the plant actively produces new stems, foliage and flowers.

Take cuttings of about 10−15 cm, making the cutting just below a leaf node. Remove most of the leaves from the cutting, only leaving two or three small leaves at the tip. Dipping the lower 3 cm or so of the cutting in hormone powder (for softwood) would enhance the formation of roots by the cutting. Plant the cuttings in a prepared pot containing well-draining soil. A mix of half of potting soil and half perlite works well. Make holes in a prepared pot and plant the cuttings with about half of the length of the cutting below the soil. A clear plastic bag can be used to seal in heat and moisture. Place the container in a partially shaded position and keep moist (not wet!). Once they are rooted (usually in about 8 weeks) they can be re-potted in a bigger pot or directly in the garden.

Plants can also be grown from seed. To break the seedcoat seeds can be lightly sanded with fine sanding paper and then soaked overnight in water to break their dormancy and kick-start germination. The seeds can then be planted in a seed tray. The rule of thumb is to plant seeds at least twice as deep than their size. Sprinkle more soil over the seed. Keep moist until they germinate. Seedlings should appear in 1−4 weeks. After a couple of more weeks, when the seedlings are large enough, they can be re-potted or planted in the garden.

Growing hibiscus from cuttings or seed can either be done indoors or outdoors. Plants, however, does best when grown in habitats and regions that best mimics its natural environment, i.e. relative warm places in sandy soils in partial shade.

References

- Bayer, C. & Kubitzki, K. 2003. Malvaceae. In: K. Kubitzki & C. Bayer (eds), The Families and Genera of Vascular Plants 5: 225–311.

- Bentley, B.L. 1977. Extrafloral nectaries and protection by pugnacious bodyguards. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 8: 407–427.

- Bester, S.P. 2022. Botanical collections in the Waterberg Mountain Complex kicks off. SANBI Gazette 7: 3–4.

- Bester, S.P., Freylinck, M. & Condy, G. 2025. Hibiscus waterbergensis. The Flowering Plants of Africa.

- Botanical Database of Southern Africa (BODATSA). Searched via https://posa.sanbi.org. Accessed June 2024.

- Buttrose, M.S., Grant, W.J.R. & Lott, J.N.A. 1977. Reversible curvature of style branches of Hibiscus trionum L., a pollination mechanism. Australian Journal of Botany 25: 567–570.

- De la Fuente, M.A.S. & Marquis, R.J. 1999. The role of ant-tended extrafloral nectaries in the protection and benefit of a Neotropical rainforest tree. Oecologia 118 (2): 192–202.

- Exell, A.W. 1959. New and little known species from the flora Zambesiaca area 9: Hibisci Novi. Boletim da Sociedade Broteriana 33 (ser.2): 165–181.

- Farnsworth, N.R., Fong, H.H.S & Diczfallusy, E. 1983. New fertility regulating agents of plant origin. International Symposium on research on the Regulation of human Fertility: Needs of developing countries and priorities for the future. Stockholm.

- Fryxell, P.A. 1968. A redefinition of the tribe Gossypieae. Botanical Gazette 129: 296–308.

- Gardening Know How. Hibiscus propagation made simple. https://www.gardeningknowhow.com/ornamental/flowers/hibiscus/hibiscus-propagation.htm. Accessed 06/01/2025.

- Germishuizen, G. & Fabian, A. 1997. Wild flowers of northern South Africa. Fernwood Press, Vlaeberg, Cape Town.

- Germishuizen, G., Meyer, N.L., Steenkamp, Y. & Keith, M. 2006. A checklist of South African Plants . South African Botanical Diversity Network Report No. 41. SABONET, Pretoria.

- Gottsberger, G. 1972. Blütenbiologische Beobachhtungen an brasilianischen Malvaceen, II. Österreichische Botanische Zeitschrift 120: 439–509.

- Hutchings, A., Scott, A.H., Lewis, G. & Cunningham, A.B. 1996. Zulu medicinal plants: an inventory. University of Natal Press, Pietermaritzburg.

- Leistner, O.A. (ed.). 2000. Seed plants of southern Africa: families and genera. Strelitzia 10. National Botanical Institute, Pretoria.

- Hanes, M.M., et al. 2024. Phylogenetic relationships within tribe Hibisceae (Malvaceae) reveal complex patterns of polyphyly in Hibiscus and Pavonia. Systematic Botany 49(1): 77−116.

- Hinsley, S.R. 2004-2020. The Malvaceae Pages. http://www.malvaceae.info. Accessed June 2024.

- Homes & Gardens. How to propagate hibiscus shrubs – expert advice for taking plant cuttings. https://www.homesandgardens.com/gardens/how-to-propagate-hibiscus. Accessed 06/01/2025.

- Koekemoer, M., Steyn, H.M. & Bester, S.P. 2023. Flowering plant families of southern Africa. Strelitzia 46. South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria.

- Le Roux, L.-N. 2008. Hibiscus calyphyllus Cav. (Malvaceae). PlantZAfrica. Online. https://pza.sanbi.org/hibiscus-calyphyllus

- Leitão, C.A.E., Meira, R.M.S.A., Azevedo, A.A., DE Araújo, J.M., Silva, K.L.F. & Collevatti, R.G. 2005. Anatomy of the floral, bract, and foliar nectaries of Triumfetta semitriloba (Tiliaceae). Canadian Journal of Botany 83: 279–286.

- Letty, C. 1962. Wild flowers of the Transvaal. Wildflowers of the Transvaal Book Fund.

- Mabberley, D.J. 1997. The Plant Book. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- McDonald, D. 2021. Waterberg Mountain Complex in focus as FBIP awards R4m Grant. FBIP website. https://fbip.co.za/news/waterberg-mountain-complex-in-focus-as-fbip-awards-large-grant/.

- McDonald, D. 2022. Waterberg Biodiversity Project botanical team haul over 500 plant specimens on first excursion. FBIP website. https://fbip.co.za/news/waterberg-botanical-team-hauls-over-500-plant-specimens/.

- Mucina, L. & Rutherford, M.C. (eds) 2006. The vegetation of South Africa, Lesotho and Swaziland. Strelitzia 19. South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria.

- Nkadimeng, F. 202. Hibiscus coddii Exell (Malvaceae). PlantZAfrica. Online. https://pza.sanbi.org/hibiscus-coddii

- Parman, N.S. & Gosgh, M.N. 1978. Anti-inflammatory activity of gossypin, a bioflavonoid from Hibiscus vitifolius L. Indian Journal of Pharmacology 10: 277–293.

- Pephu, N. 2013. Hibiscus tiliaceus L. (Malvaceae). PlantZAfrica. Online. https://pza.sanbi.org/hibiscus-tiliaceus

- Pfeil, B.E., Brubaker, C.L., Craven, L.A. & Grisi, M.D. 2002. Phylogeny of Hibiscus and the tribe Hibisceae (Malvaceae) using chloroplast DNA sequences of ndhF and rpl16 intron. Systematic Botany 27(2): 333–350.

- Phillipson, P.B. 1992. Hibiscus ferrugineus. The Flowering Plants of Africa 52: t. 2057.

- Plants of the World Online. Hibiscus L. https://powo.science.kew.org/taxon/urn:lsid:ipni.org:names:328182-2. Accessed on 28 February 2024.

- Pole Evans, I.B. 1931. Hibiscus praeteritus. The Flowering Plants of South Africa 11: t. 436.

- Retief, E. & Herman, P.P.J. 1997. Plants of the northern provinces of South Africa: keys and diagnostic characters. Strelitzia 6. National Botanical Institute, Pretoria.

- The Gardener. Growing hibiscuses. https://www.thegardener.co.za/the-gardener/hh/growing-hibiscuses/. Accessed May 2024.

- Van Wyk, B.-E. & Gericke, N. 2000. People's plants. Briza Publications, Pretoria.

- Van Wyk, B-E. 2005. Food plants of the World. Briza Publications, Pretoria.

- Victor, J.E. 2006. Hibiscus waterbergensis Exell. National Assessment: Red List of South African Plants. http://redlist.sanbi.org/species.php?species=2585-107.

- Viljoen, C. 2010. Hibiscus pedunculatus L.f. (Malvaceae). PlantZAfrica. Online. https://pza.sanbi.org/hibiscus-pedunculatus.

- Vogel, S. 2000. The floral nectaries of Malvaceae sensu lato - a conspectus. Kurtziana 28: 155–171.

- Wadley, L., Willemse, L., Baytopp, K., Swart, J., Heymans, J. Tarboton, W. & Tarboton, M. 2021. Wild Flowers of the Waterberg. Mapula Trust.

Credits

SP Bester

National Herbarium, Pretoria,

Foundational Research and Services Division, Botanical Research Directorate

February 2025

Acknowledgements: the author sincerely thanks the photographers who made their images available for use: A Frisby, J Gallagher, G Jamie, J Kalwij, L Lindenthal, M Pienaar, M Popp, SAPlants@Wikicommons and T van der Merwe (see individual acknowledgements in captions of images), and the FBIP Waterberg Mountain Complex Project for facilitating observations of this species made by the author during the project.

Plant Attributes:

Plant Type: Shrub

SA Distribution: Limpopo

Soil type: Sandy, Loam

Flowering season: Early Summer, Late Summer

PH:

Flower colour: Red

Aspect: Full Sun, Morning Sun (Semi Shade), Afternoon Sun (Semi Shade)

Gardening skill: Average

Special Features:

Horticultural zones

Rate this article

Article well written and informative

Rate this plant

Is this an interesting plant?

Login to add your Comment

Back to topNot registered yet? Click here to register.